Testing With Intent: Testing The Database With Interfaces

Throughout this testing series I’ve talked about using wrappers and adapters to

manage side-effects. In this post, I want to expand on that theme, and take the

opportunity to do a worked example. This example is based on the first part of

an October 2018 talk I gave at

London Gophers.

Interfaces

Why are integration tests slow? They talk to real services.

But what if we could run our tests with a different, faster, database?

Interfaces are the key to that.

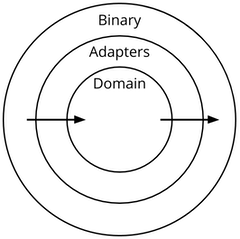

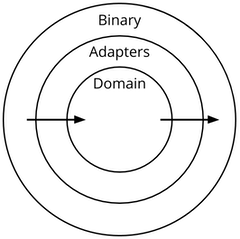

Hexagonal Architecture

This gets called, “hexagonal architecture”, “ports and adapters”,

“functional-core-imperative-shell”. They’re all the same thing. Hexagonal

architecture is a way to structure your app to make the best use of interfaces.

It starts with our domain (business logic) in the core. Then we add on adapters

for each protocol: rest, smtp, sql. And finally, we build the mother of all

adapters, an executable binary.

No Outward Dependencies

Structuring our app with Hexagonal Architecture, we have to manage dependencies.

Only outer layers can import inner layers. Inner layers can never import the

outer. For example our business logic can never import the SMTP wrapper.

So, the binary imports our adapters. The adapters import our domain logic. Our

domain provides interfaces for the adapters to implement. These are the “ports”

in ports-and-adapters. This all works really well with Go’s interface system

Example

Lately, during the break at London Gophers there has been a quiz. I’ve been

enjoying that, so for this example let’s build a small quiz app. It’ll be

simple, but will have a database connection, and some small domain logic.

The app structure is:

$ tree .

.

├── main.go

├── db

│ └── db.go

└── quiz

├── answer.go <- What we're testing

├── quiz.go

├── answer_test.go <- The tests we're writing

├── integration_test.go <- Where the magic happens

└── unit_test.go <- Magic also happens here

2 directories, 7 files

There are three main components to this app. The main.go file, which builds

our binary. The db package is our real database adapter. The quiz package

contains our domain logic.

package quiz

type AnswerDB interface {

SaveAnswer(a Answer) error

GetAnswer(questionID string) (Answer, error)

}

func SubmitAnswer(d AnswerDB, a Answer) error {

err := validateAnswer(a)

return d.SaveAnswer(a)

}

Because DBs are a slow external adapter, we wrap the DB in an interface. Our

domain logic uses that interface. AnswerDB is our interface. It can save and

read answers. SubmitAnswer is a simple “action” which does some validation and

saves.

This is the basic app structure. If we were doing a rest API, you

could see that fitting in as another adapter, like the database.

How do we test all this?

package quiz_test

func TestSubmitAnswer_SavesValidAnswers(t *testing.T) {

// Connect to our test db, and clean it up after

db := Setup(t)

defer Cleanup(t, db)

// More test here ...

}

This is the skeleton of a test for the domain logic. Normally for integration

tests, it would be better to do these at the “rest” layer, but for this example

we’ll do it on the domain logic.

The important bit here is the Setup and Cleanup. Setup creates a test database and

Cleanup does cleanup afterwards. We need to implement these.

The rest of the test is a straightforward Arrange/Act/Assert flow:

package quiz_test

func TestSubmitAnswer_SavesValidAnswers(t *testing.T) {

// Connect to our test db, and clean it up after

db := Setup(t)

defer Cleanup(t, db)

// Arrange our test data

a := quiz.Answer{

QuestionID: "question1",

ChoiceID: "choice1",

}

// Act

quiz.SubmitAnswer(db, a)

// Assert it was saved to the db

result, err := db.GetAnswer(a.QuestionID)

if result != a || err != nil {

t.Errorf("Expected valid answer to be saved.")

}

}

As a side note, one of the things which might be bad, is that we have to use the

GetAnswer method on the database to check the results. If we don’t need a

GetAnswer method we would be forced to add an extra test-helper methods to the

db.

Now, how do we implement Setup and Cleanup? To make our tests fast, we can

implement them using a simple test double. In this case we’re using a fake DB:

func Setup(t *testing.T) quiz.AnswerDB {

return &fakeDB{storage: map[string]string{}}

}

func Cleanup(t *testing.T, db quiz.AnswerDB) {

// Noop!

}

...

The fakeDB’s setup is quite simple. Just make and return a new fake db

instance. In this case, there is nothing to do, so the cleanup doesn’t exist. If

you’re using a global or any singletons, you need to reset those in the

Cleanup function.

fakeDB’s implementation is pretty basic. It is an in-memory implementation of

the database, which is fast and portable. Nothing to set up. You can get quite a

ways with ID-keyed maps.

...

type fakeDB struct {

storage map[string]string

}

func (f fakeDB) SaveAnswer(a quiz.Answer) error {

f.storage[a.QuestionID] = a.ChoiceID

return nil

}

func (f fakeDB) GetAnswer(questionID string) (quiz.Answer, error) {

choiceID, ok := f.storage[questionID]

if !ok {

return quiz.Answer{}, fmt.Errorf("answer not found")

}

return quiz.Answer{QuestionID: questionID, ChoiceID: choiceID}, nil

}

For more database-heavy workflows, it makes sense to use a stub (instead of a

fake). A stub will help you test potential error-conditions, and by providing

pre-set responses you can avoid making the fake too complex.

Throughout this testing series I’ve talked about using wrappers and adapters to manage side-effects. In this post, I want to expand on that theme, and take the opportunity to do a worked example. This example is based on the first part of an October 2018 talk I gave at London Gophers.

Interfaces

Why are integration tests slow? They talk to real services.

But what if we could run our tests with a different, faster, database? Interfaces are the key to that.

Hexagonal Architecture

This gets called, “hexagonal architecture”, “ports and adapters”, “functional-core-imperative-shell”. They’re all the same thing. Hexagonal architecture is a way to structure your app to make the best use of interfaces.

It starts with our domain (business logic) in the core. Then we add on adapters for each protocol: rest, smtp, sql. And finally, we build the mother of all adapters, an executable binary.

No Outward Dependencies

Structuring our app with Hexagonal Architecture, we have to manage dependencies. Only outer layers can import inner layers. Inner layers can never import the outer. For example our business logic can never import the SMTP wrapper.

So, the binary imports our adapters. The adapters import our domain logic. Our domain provides interfaces for the adapters to implement. These are the “ports” in ports-and-adapters. This all works really well with Go’s interface system

Example

Lately, during the break at London Gophers there has been a quiz. I’ve been enjoying that, so for this example let’s build a small quiz app. It’ll be simple, but will have a database connection, and some small domain logic.

The app structure is:

$ tree .

.

├── main.go

├── db

│ └── db.go

└── quiz

├── answer.go <- What we're testing

├── quiz.go

├── answer_test.go <- The tests we're writing

├── integration_test.go <- Where the magic happens

└── unit_test.go <- Magic also happens here

2 directories, 7 files

There are three main components to this app. The main.go file, which builds

our binary. The db package is our real database adapter. The quiz package

contains our domain logic.

package quiz

type AnswerDB interface {

SaveAnswer(a Answer) error

GetAnswer(questionID string) (Answer, error)

}

func SubmitAnswer(d AnswerDB, a Answer) error {

err := validateAnswer(a)

return d.SaveAnswer(a)

}

Because DBs are a slow external adapter, we wrap the DB in an interface. Our

domain logic uses that interface. AnswerDB is our interface. It can save and

read answers. SubmitAnswer is a simple “action” which does some validation and

saves.

This is the basic app structure. If we were doing a rest API, you could see that fitting in as another adapter, like the database.

How do we test all this?

package quiz_test

func TestSubmitAnswer_SavesValidAnswers(t *testing.T) {

// Connect to our test db, and clean it up after

db := Setup(t)

defer Cleanup(t, db)

// More test here ...

}

This is the skeleton of a test for the domain logic. Normally for integration tests, it would be better to do these at the “rest” layer, but for this example we’ll do it on the domain logic.

The important bit here is the Setup and Cleanup. Setup creates a test database and Cleanup does cleanup afterwards. We need to implement these.

The rest of the test is a straightforward Arrange/Act/Assert flow:

package quiz_test

func TestSubmitAnswer_SavesValidAnswers(t *testing.T) {

// Connect to our test db, and clean it up after

db := Setup(t)

defer Cleanup(t, db)

// Arrange our test data

a := quiz.Answer{

QuestionID: "question1",

ChoiceID: "choice1",

}

// Act

quiz.SubmitAnswer(db, a)

// Assert it was saved to the db

result, err := db.GetAnswer(a.QuestionID)

if result != a || err != nil {

t.Errorf("Expected valid answer to be saved.")

}

}

As a side note, one of the things which might be bad, is that we have to use the

GetAnswer method on the database to check the results. If we don’t need a

GetAnswer method we would be forced to add an extra test-helper methods to the

db.

Now, how do we implement Setup and Cleanup? To make our tests fast, we can

implement them using a simple test double. In this case we’re using a fake DB:

func Setup(t *testing.T) quiz.AnswerDB {

return &fakeDB{storage: map[string]string{}}

}

func Cleanup(t *testing.T, db quiz.AnswerDB) {

// Noop!

}

...

The fakeDB’s setup is quite simple. Just make and return a new fake db

instance. In this case, there is nothing to do, so the cleanup doesn’t exist. If

you’re using a global or any singletons, you need to reset those in the

Cleanup function.

fakeDB’s implementation is pretty basic. It is an in-memory implementation of

the database, which is fast and portable. Nothing to set up. You can get quite a

ways with ID-keyed maps.

...

type fakeDB struct {

storage map[string]string

}

func (f fakeDB) SaveAnswer(a quiz.Answer) error {

f.storage[a.QuestionID] = a.ChoiceID

return nil

}

func (f fakeDB) GetAnswer(questionID string) (quiz.Answer, error) {

choiceID, ok := f.storage[questionID]

if !ok {

return quiz.Answer{}, fmt.Errorf("answer not found")

}

return quiz.Answer{QuestionID: questionID, ChoiceID: choiceID}, nil

}

For more database-heavy workflows, it makes sense to use a stub (instead of a fake). A stub will help you test potential error-conditions, and by providing pre-set responses you can avoid making the fake too complex.