The Magic of the Merkle Tree

One of the most exciting data structures in recent years has been the rise in

application of the Merkle Tree. The draw of Merkle trees can be summarized in

two words, “scalable verification”. Given that description, it’s not surprising

that they’re finding the most use in applications such as: blockchain,

distributed build systems, version-control, and file-sharing.

What are they?

Like many other trees, Merkle trees offer substantial scalability. By

drastically reducing the number of nodes at each level, it becomes possible to

work with large amounts of data. However, in a binary search tree, or a b+

tree, you have to have a certain level of trust in the storage medium. You have

to be able to trust that the leaf-nodes are not manipulating data, or

misbehaving. The Merkle tree allows you to recursively verify the data from

each level of the tree. In practice, this means that if the root node can be

verified, the whole tree is valid.

This recursive verification is done by making the key of each node a hash of

that node’s contents. Each node becomes content-addressable. Higher nodes in

the tree are keyed with a hash of the hashes of their children. Verifying that

a leaf node is included means we only need to process a logarithmic number of

nodes.

The drawbacks of Merkle trees (against other types of trees) include higher CPU

usage and memory footprints. With a binary search tree, generating the root

node is quite easy, but with a Merkle tree you have to compute, and store a

hash at each node. For large trees this can add up, however this can be

mitigated by choosing an appropriate branching factor. Furthermore, they will

perform badly when searching for a particular value in the tree. Merkle trees

are not search trees.

How do they work?

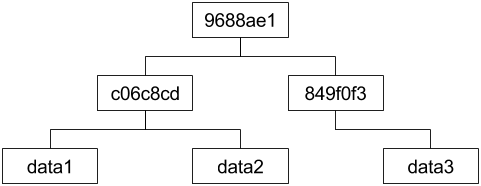

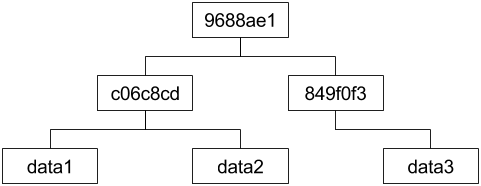

A basic diagram of a merkle tree would look like:

Here we have a branching factor of 2, so each node has 2 children. We

hash data1, and data2, to get the c06c8cd internal node.

Similarly for data3, to get 849f0f3. Then we hash those two

internal nodes to get our root node 9688ae1. If we replace data3,

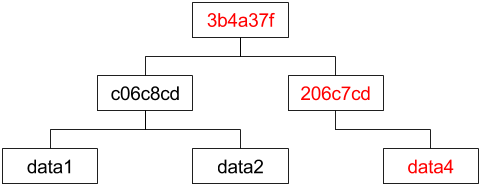

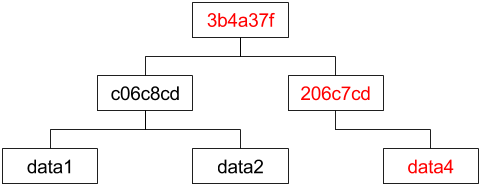

with data4, the tree would change to be:

Note, the hash of data4 has changed to 206c7cd. This change then

propagates up the tree, causing the root node to become 3b4a37f.

But, note the data1/data2 subtree has remained unchanged.

One of the nice side-effects of each node being addressed via a hash of its

contents, is that Merkle trees lend themselves supremely to structural sharing,

and are naturally immutable. When you add a new node to the tree, you get a new

tree. But, because the nodes cannot change we can re-use any unchanged nodes,

to save on memory churn. This makes Merkle trees an extremely good fit for most

functional languages which exploit structural sharing to implement immutable

data structures, as well as concurrent usage. These properties also makes

writing correct caching systems very easy.

Concurrent read access is easy, because each reference to a root node is also a

reference to a complete snapshot of the tree. Concurrent writes require a lock

on the root node. Because the root node contains a hash of all the content of

the entire tree, any change to the tree will require generating a new root node

and updating the tree to use it. If we lock the root node, we can be sure that

no one else is able to simultaneously update the root node which would cause a

race condition.

Choosing a branching factor

Choosing a branching factor is an important part of managing the overhead of a

Merkle tree. Choosing a good branching factor depends on several properties of

your system, and there is no right answer for 100% of situations. The branching

factor you should use depends on:

- Size of the hash algorithm

- Expected number of nodes

- Retrieval latency and transfer speed of your storage

- Ratio of writes to reads

Though not a Merkle tree, Clojure’s persistent immutable tree implementation

(ideal hash trees) shares many aspects with a Merkle tree, so it can be a good

example of the tradeoffs involved. Clojure’s tree implementation does not use a

cryptographically secure choice for it’s hashing algorithm, so it is not a good

choice for a Merkle tree. However, the tradeoff is that it has excellent

performance. Because each hash takes up 32 bits, on a 64-bit processor we can

fit two hashes into an L2 cache line. Furthermore, the hash only being 32-bits

means that there is a high collision frequency, which is a bad choice for a

Merkle tree implementation. A better choice would be SHA, or some other hash

algorithm without collisions. For a cryptographically-secure hash designed to

perform well on 64-bit platforms, some implementations use Tiger hashes.

Clojure trees also have quite a high branching factor of 32. With large numbers

of leaves, a higher branching factor means a smaller tree height, and fewer

internal nodes. When you search through the tree, you need fewer round-trips to

reach the leaf nodes, but each node-lookup transfers more data (32 pointers,

plus other data). This tradeoff is perfect if you have a high data-transfer

rate, but also higher latency of each round-trip. Clojure has chosen this

tradeoff because it implements arrays using a tree data structure. The very

high branching factor means that lookups in the “array” are very approximately

constant time. Different tradeoffs may be more appropriate for your

implementation and usage. For example, larger branching factors mean fewer

internal nodes, but adding or removing leaves means changing a higher

percentage of the internal nodes, and rehashing more of the tree, so a

consideration is the frequency of updates to your tree.

Where are they used?

If you’ve followed along up until now, I’m happy to say you understand the

fundamentals of: blockchains; many incremental build systems; and many aspects

of git version-control.

At it’s core, Bitcoin (and Ethereum, and other blockchains), are distributed

Merkle trees. Each “block” is a new root node for the tree which includes new

transactions hashed into it, and nodes race to hash the transactions and

generate the new root node fastest.

Incremental builds, hash the inputs of each build step. If the inputs haven’t

changed, entire branches of the tree can be cached and reused, improving the

speed of following builds.

One of the most exciting data structures in recent years has been the rise in application of the Merkle Tree. The draw of Merkle trees can be summarized in two words, “scalable verification”. Given that description, it’s not surprising that they’re finding the most use in applications such as: blockchain, distributed build systems, version-control, and file-sharing.

What are they?

Like many other trees, Merkle trees offer substantial scalability. By drastically reducing the number of nodes at each level, it becomes possible to work with large amounts of data. However, in a binary search tree, or a b+ tree, you have to have a certain level of trust in the storage medium. You have to be able to trust that the leaf-nodes are not manipulating data, or misbehaving. The Merkle tree allows you to recursively verify the data from each level of the tree. In practice, this means that if the root node can be verified, the whole tree is valid.

This recursive verification is done by making the key of each node a hash of that node’s contents. Each node becomes content-addressable. Higher nodes in the tree are keyed with a hash of the hashes of their children. Verifying that a leaf node is included means we only need to process a logarithmic number of nodes.

The drawbacks of Merkle trees (against other types of trees) include higher CPU usage and memory footprints. With a binary search tree, generating the root node is quite easy, but with a Merkle tree you have to compute, and store a hash at each node. For large trees this can add up, however this can be mitigated by choosing an appropriate branching factor. Furthermore, they will perform badly when searching for a particular value in the tree. Merkle trees are not search trees.

How do they work?

A basic diagram of a merkle tree would look like:

Here we have a branching factor of 2, so each node has 2 children. We

hash data1, and data2, to get the c06c8cd internal node.

Similarly for data3, to get 849f0f3. Then we hash those two

internal nodes to get our root node 9688ae1. If we replace data3,

with data4, the tree would change to be:

Note, the hash of data4 has changed to 206c7cd. This change then

propagates up the tree, causing the root node to become 3b4a37f.

But, note the data1/data2 subtree has remained unchanged.

One of the nice side-effects of each node being addressed via a hash of its contents, is that Merkle trees lend themselves supremely to structural sharing, and are naturally immutable. When you add a new node to the tree, you get a new tree. But, because the nodes cannot change we can re-use any unchanged nodes, to save on memory churn. This makes Merkle trees an extremely good fit for most functional languages which exploit structural sharing to implement immutable data structures, as well as concurrent usage. These properties also makes writing correct caching systems very easy.

Concurrent read access is easy, because each reference to a root node is also a reference to a complete snapshot of the tree. Concurrent writes require a lock on the root node. Because the root node contains a hash of all the content of the entire tree, any change to the tree will require generating a new root node and updating the tree to use it. If we lock the root node, we can be sure that no one else is able to simultaneously update the root node which would cause a race condition.

Choosing a branching factor

Choosing a branching factor is an important part of managing the overhead of a Merkle tree. Choosing a good branching factor depends on several properties of your system, and there is no right answer for 100% of situations. The branching factor you should use depends on:

- Size of the hash algorithm

- Expected number of nodes

- Retrieval latency and transfer speed of your storage

- Ratio of writes to reads

Though not a Merkle tree, Clojure’s persistent immutable tree implementation (ideal hash trees) shares many aspects with a Merkle tree, so it can be a good example of the tradeoffs involved. Clojure’s tree implementation does not use a cryptographically secure choice for it’s hashing algorithm, so it is not a good choice for a Merkle tree. However, the tradeoff is that it has excellent performance. Because each hash takes up 32 bits, on a 64-bit processor we can fit two hashes into an L2 cache line. Furthermore, the hash only being 32-bits means that there is a high collision frequency, which is a bad choice for a Merkle tree implementation. A better choice would be SHA, or some other hash algorithm without collisions. For a cryptographically-secure hash designed to perform well on 64-bit platforms, some implementations use Tiger hashes.

Clojure trees also have quite a high branching factor of 32. With large numbers of leaves, a higher branching factor means a smaller tree height, and fewer internal nodes. When you search through the tree, you need fewer round-trips to reach the leaf nodes, but each node-lookup transfers more data (32 pointers, plus other data). This tradeoff is perfect if you have a high data-transfer rate, but also higher latency of each round-trip. Clojure has chosen this tradeoff because it implements arrays using a tree data structure. The very high branching factor means that lookups in the “array” are very approximately constant time. Different tradeoffs may be more appropriate for your implementation and usage. For example, larger branching factors mean fewer internal nodes, but adding or removing leaves means changing a higher percentage of the internal nodes, and rehashing more of the tree, so a consideration is the frequency of updates to your tree.

Where are they used?

If you’ve followed along up until now, I’m happy to say you understand the fundamentals of: blockchains; many incremental build systems; and many aspects of git version-control.

At it’s core, Bitcoin (and Ethereum, and other blockchains), are distributed Merkle trees. Each “block” is a new root node for the tree which includes new transactions hashed into it, and nodes race to hash the transactions and generate the new root node fastest.

Incremental builds, hash the inputs of each build step. If the inputs haven’t changed, entire branches of the tree can be cached and reused, improving the speed of following builds.